Demei's View - Wine Communication from a Chinese Winemaker

We have an ancient saying in China, which literally means that when you are climbing a mountain, you always think that the mountains surrounding you are taller than yours. This saying criticises those who are quick to feel jealous about what other people have and overlook what they already own.

People tend to get especially pessimistic when they don’t know what to do when facing difficulties. Unfortunately, the cruel reality is that when they finally reach the top of the ‘higher mountain’ they saw before, they usually find that it’s not that tall at all — perhaps even lower than the old mountain which they had given up climbing so hastily.

Such unnecessary ‘inferiority complex’ is common in today’s Chinese wine market.

The year 2015 has half passed by now. Usually for the wine trade, the first half-year is much ‘lighter’ in business than the latter half. When the market was good, people don’t really mind the quiet half-year, instead they wait patiently and put all their strength into the peak season.

However, as the wine market has been sluggish for several continuous years, many used-to-be wine practitioners have long left the business. Those who are still dreaming of becoming rich with wine have started to calculate the trade figures in a more and more frequent manner, terrified of missing any new trend.

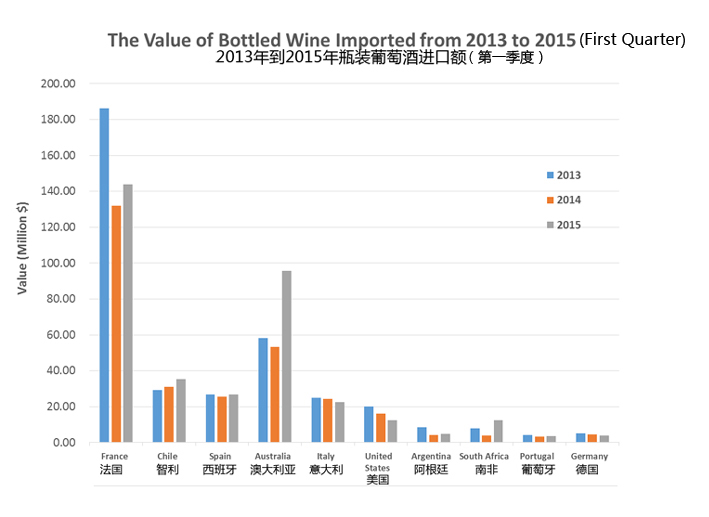

And the latest topic among the Chinese wine trade is that during the first quarter, import figures are looking very promising; a 30% increase year-on-year during the first three months, close to the same period in 2013 — the first quarter that set the highest record in the market history.

The same boring set of figures can lead to different conclusions depending on who is analyzing it. For the French producers, they see the rapid increase in volumes of imported wines Australia, South Africa and Chile, and they are complaining about not enjoying any cuts in tariffs. Australia and the US, I suppose, must feel quite bitter about French wines occupying the major share of Chinese market while owning far smaller share in the global market.

So how come all of a sudden Chilean and Australian wines are enjoying such a boost in imports? The average price of Australian wines has always been higher than French wines so clearly price is not the reason. I consulted a few major wine importers, and they told me that there wasn’t obvious increase in sales of wines from these two countries.

Well then, what was the reason behind the sudden increase of imports?

From the beginning of 2015, Chilean wines have started to enjoy tariff exemption while the tariff for Australian wines will be gradually reduced to zero in the next few years.

The good news has brought about massive import orders from investors who are confident in the rise of wine consumption in China. In the meantime, however, there is no apparent uptake in wine consumption in the market, according to a few major traditional wine importers I have spoken to; hence the mismatch of import figures and the actual sales.

The wine market has never lacked opportunists. Seeing the current situation, I can’t help thinking of Bordeaux en primeur 2009, a vintage with its price skyrocketed due to the sudden flooding in of Chinese opportunist investors. The fine balance between supply and demand in Bordeaux was broken by these intruders, who have never sold en primeur wines, if not any wines before.

Immediately they found themselves trapped in difficulties and risks after leaping into the market, and many of them soon chose to flee. The local merchants haven’t even got a chance to calculate how much money they have earned, only to find that many Chinese buyers have already abandoned their orders. The dark days are still too painful to reflect, not to mention many are still suffering from the residual impact.

Wine investment is an interesting financial concept. When highly priced wines are no longer as popular as before, the Chinese trade has come to realise the need to re-explore the potential of mass consumption. At this right moment, are Chinese consumers suddenly interested in Chilean and Australian wines? Possibly it is the importers with integrated capital, not consumers, who are more intrigued by the move of market.

The hidden risk behind the sudden surge of imports lies in the imbalance between consumption and supplies, which will almost certainly result in wines stuck in distribution channels. If that happens, not only will importers take a heavy hit, but the reputation of a region or a brand will also be at risk, due to disordered competition.

The success of those French ‘star chateaux’ in China has also benefited other French wineries, making French wines generally very well-known among Chinese consumers. Since 2012, as the market demands for Cru Classes were fading, so did the bubbles created by the celebrity effect. Currently the imports, distribution and consumption of French wines in China are actually at a reasonable balance.

As a matter of fact, the French wine trade has no need to panic about other wine countries’ sudden growths in market shares in China. On the contrary, the producers of these wines which come flooding in should be alarmed; if the consumers are not well-informed and not ready to accept them, the artificially heated imports may soon die down again.

A good example is that Australian wine trade is putting more and more efforts in promoting its wines in China. The official body Wine Australia has not only set up a China office, but also organised a series of nation-wide wine activities. They have also certified many educators to talk about Australian wine culture in China.

These moves can be seen as positive response from the trade to the gradual elimination of tariffs agreed by both governments. Thanks to these activities, at least many of my friends who started off drinking French wines are gradually moving towards Australian wines.

Are other mountains really taller than yours? To answer that, you need to know the height of the mountain you’re on. When you are asked this question, you should know that you are gently reminded not to be so quick to feel sorry for yourself. You need to first realise what you have and what your target is, before going any further.

I would make the same suggestion to the Chinese winemakers; when making efforts to raise the quality of your products, it is indeed necessary to study from the experience of other countries. Simply envying others’ success, however, will take you nowhere.

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit