We’ve read the words hundreds of times in wine descriptions; smoky, flinty, oyster shell, chalky, silex, slate, quartz... Close your eyes and you can feel your mouth water at the thought of a taut, angular wine that tastes of the stones its roots struggled through. And it’s easy to understand what Burgundy winemaker Mark Haisma means when he says, ‘For me, minerality is the opposite of a fat, frutti-tutti wine that lacks tension.’

and adapted under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

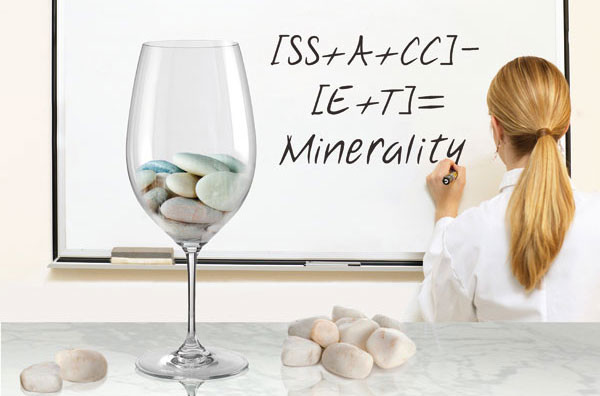

But minerality is a concept that causes more arguments and misunderstandings in wine than pretty much any other. Most wine scientists would firmly argue that there is a distinct lack of evidence that it even exists, as no single molecule equates to a mineral wine. Most wine lovers, on the other hand, would snort into their Chablis and counter that no other word can sum up that quality of wet stone verticality, where you can almost cut your tongue on the flavours, as succinctly as the word mineral.

'If enough people agree on a wine tasting term,' says aroma expert Alexandre Schmitt, 'I'm inclined to say that the professionals are being a little snippy to disagree with it.'

Winemaker and consultant Denis Dubourdieu is less certain. ‘Minerality is an image, not a reality… but sometimes an incorrect image is easier to talk about than the reality, and so it becomes accepted.’

Alex Maltman, a professor of geology as well as a winemaker in the UK, has gone even further, saying, ‘Any minerals that could make it into wine are in amounts too small to be tasted, and they are pretty much tasteless anyway.’

Over the past 18 months, researchers from Lincoln University in New Zealand and Bordeaux and Burgundy oenology faculties in France, have waded in to the debate, carrying out both sensory and chemical tests to determine perceived minerality in Sauvignon Blanc wines from Marlborough, Sancerre, Bordeaux and Burgundy (Saint Bris). Studies in Chardonnay and Riesling are getting started. The aim is not purely academic; wines described as 'mineral' are often priced more highly than their peers, so it's worth knowing what you're paying for - and an understanding of the components of such a sought-after quality could help winemakers produce better wines.

The study looks at several key questions. Specifically, is minerality a smell or a taste, or is it tactile (to do with mouth feel, so a purely physical reaction)? Are there really links with the soil? Or is our perception of minerality linked instead to high acidity, or even unripe fruit and some ‘reductive’ characteristics that come essentially with bottle ageing, when contact with oxygen is avoided?

Until now, any arguments have been largely based on anecdotal evidence – this is the first major scientific study. It concentrates on wines from the 2010 vintage, with 63 wine professionals split almost evenly between the two countries, running perception and chemical tests on a large number of sample wines that were tested in both France and New Zealand.

The full results will be published in a few months, but I was sent the initial findings last week. They show up a few surprises, most notably that the hypothesis that French wines would be perceived as more mineral did not prove to be true – although the type of minerality between the two countries was different. The New Zealand wines scored more highly on the ‘fruity’ and ‘green’ scale, while the French had more ‘sour’ and ‘bitter’ characteristics (a quality often more kindly referred to as ‘noble bitterness’).

There was plenty of data to suggest that a relative absence of fruit increased the perception of minerality, particularly when combined with high acidity/low pH. That leads to the rather uncomfortable suggestion that when we taste ‘minerality’ what we actually perceive is unripe fruit, and therefore an absence of volatile thiols and esters that are responsible for many of the fruity aromas in wine. Perhaps most damagingly to the pro-mineral camp, there are links drawn between a rise in the use of the term mineral (by critics and consumers) and a rise in the use of screw-caps as a closure, which is more reductive than natural cork, and therefore emphasises the lead/graphite characteristics associated with a sulphide reductive character.

There is some hope for traditionalists, though, as limestone and chalky soils (arguably the natural home of the greatest whites, from Chablis to Sancerre to Champagne) are alkaline, so produce wines with a higher total acidity and lower pH. And most importantly perhaps, the majority of wine professionals carrying out the study all agreed that there was a definite perception of minerality as a smell and a taste, suggesting that it can be considered a valid tasting term.

Work on identifying the specific molecules, and how minerality relates to physical and chemical components of a wine such as (stick with me) organic acids, wine pH, total acidity, reducing sugars, ethanol, sulphur dixoide, concentration of thiols and transition metal elements will be released in June. But these early findings have led Wendy Parr, Senior Research Officer for the New Zealand study, to a greater confidence in the term. ‘My own view, based on observation of wine evaluations by others and on our data, is that perception of minerality differs, including among very experienced wine people. I do think that a 'flinty' note exists, and I also think that (minerality) is a complex combination of sensory stimulation involving taste, texture/mouth-feel elements, and aroma. Having said that, I also get the feeling that some wine 'judges' use the term mineral rather freely, and it gets loosely allocated to low-level reductive phenomena, and the combination of low flavour and high acidity.’

Winemakers, equally, remain convinced that they are not chasing a ghost. Jonathan Ducourt, a wine producer in the Entre deux Mers region of Bordeaux, puts it beautifully when he describes minerality as ‘an aromatic support, like salt on a rumpsteak’.

Columnist Introduction

Jane Anson is Bordeaux correspondent for Decanter, and has lived in the region since 2003. She is author of Bordeaux Legends, a history of the First Growth wines (October 2012 Editions de la Martiniere), the Bordeaux and Southwest France author of The Wine Opus and 1000 Great Wines That Won’t Cost A Fortune (both Dorling Kindersley, 2010 and 2011). Anson is contributing writer of the Michelin Green Guide to the Wine Regions of France (March 2010, Michelin Publications), and writes a monthly wine column for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she lived from 1994 to 1997. Accredited wine teacher at the Bordeaux Ecole du Vin, with a Masters in publishing from University College London.

Click here to read all articles by Jane Anson>>

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit