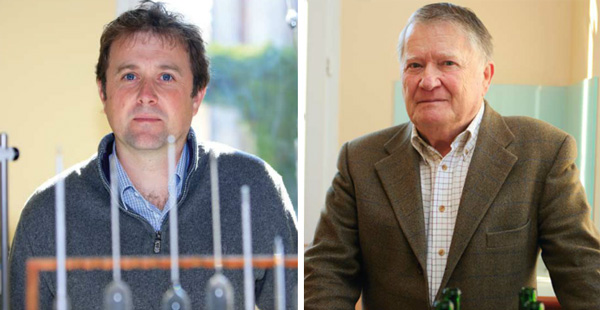

Eric Boissenot is both the best known and least known of all winemakers in Bordeaux. Together with his father Jacques, he makes wine at a good two-thirds of 1855 classified estates, including all four Médoc First Growths. And yet sit next to him at a dinner, and you’d better have brushed up on your current affairs/politics/latest movie releases, because Boissenot certainly isn’t going to be the one providing the small talk.

His reticence to push himself forward is almost as legendary as his winemaking skills, but there is one subject in which, if you can get him to talk about it, he is utterly fluent; the Médoc. This is the place where Boissenot has spent almost his entire personal and professional life – and the contours of its land, both visible and hiding beneath the surface, is where he feels most confident.

Boissenot has taught me more about what makes the wines of this region so multi-faceted than anybody, with information gleaned piecemeal from tagging along on client visits with everyone from Saint Pierre to Brane-Cantenac and Chateau Margaux, from interviewing him in his low-key laboratory in a forlorn Médoc town, and from his classes on the subject at the Bordeaux faculty of oenology (you have to listen closely, because even in a lecture hall with 45 attentive students, Boissenot doesn’t do a whole lot of voice projection).

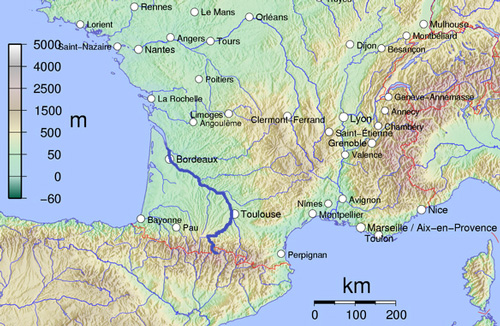

First things first. To understand the wines of the Médoc, you have to understand its geography. And specifically its hugely complicated geology, that comes alive only when you taste the wines that have been grown in the different bands of gravel, clay, sand and limestone that underpin the 16,000 hectares of vines grown in concentrated patches from the town of Blanquefort up to the remote outposts of Lesparre-Médoc and St-Vivien-de-Médoc, with the best chateaux strung like a diamond necklace along the river’s edge.

There are some things about this triangle of land (that stretches 100 kilometres from north to south, and covers in total 40,000 hectares, with only a minority suitable for vine growing) that are immediately obvious just by driving, walking, or cycling through. Firstly, this is low-lying country. Even the highest points barely climb above 35 metres above sea level, and the majority stands between 10 and 20 metres. But the usual rules about altitude are turned on their head here. Chateau Latour, for example, is the lowest lying First Growth, at only 13 metres altitude, and yet it produces wines of exquisite beauty.

The second thing you will notice is the water. Not only do you have the Garonne river trailing you to the east, eventually becoming the Gironde Estuary, but there is the constant influence of the Atlantic Ocean to the west (you don’t see it from the vineyards, bordered as it is by sandy beaches and a vast tract of pine forest) but you feel it, and more importantly the vines feel its softening influence, its constantly moving currents of air. And besides these two significant bodies, there are countless little streams of water – the Médoc Jalles – that crisscross the land, searching for a route back to the Garonne.

and adopted under Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license

And beyond all of this, there is the water that shaped this entire land over millennia, by turns submerging it, then retreating, each time leaving its mark. It is this memory of water that has left, at the deepest level of Médoc terroir, a bedrock of limestone, with oyster shell marls. The oldest limestone in the Médoc is in Saint Estephe (with pockets in Margaux), dating back over 1.5 million years, sitting under a layer of gravel that was brought from the Pyrenées mountains, deposited there by the Garonne river that had already begun to carve its path to the ocean by this route, leaving its alluvial deposits to the west, because the Right Bank of the river had already risen higher. A succession of glacial periods led the water levels to again retreat and rise, each time leaving new geological deposits, and the formation of terraces and gravel outcrops dating from two separate and distinct geological eras.

There was at one time an abundance of these terraces – at least six or seven – spread all over the peninsula, with large and steep valleys, until the arrival of two catastrophic phenomena 10,000 years ago – firstly sustained strong winds over centuries that wore the gravel down, eventually forming sandier soils, particularly on the Atlantic side and over to the middle sections of Listrac and Moulis, and secondly water rising and covering the precious terraces – again largely to the western, Atlantic side.

‘What this meant is that we lost precious vine-growing surfaces, although we were lucky not to lose more,’ says Boissenot. ‘Even today, dig one metre down and you’ll find gravel, but the exceptional parts of the Médoc are not as numerous as they once were, and the ones that remain are genuine treasures’.

So why is all of this so extraordinary for wine? ‘The communal point for all great soils is that they allow just the right amount of nutrition to the vines, ensuring that they are sufficiently supplied with nutrients, but that nothings comes too easy. Vines need to struggle to reveal the best of themselves. In the Médoc, ironic perhaps with all the water that surrounds it, we have dry soils – countless different shapes and sizes of gravel, punctuated by limestones and sands. And the vines compensate by growing deep roots. If there is heavy rainfall, the water is quickly diluted. The dominance of dry, gravelly soil is the key to understanding why the Cabernet Sauvignon grape is the soul of the Médoc, the diviner of the soil below the surface, and the most perfect expression of its complexity.’

Boissenot talks about the different terroirs like he is discussing children in the playground; St Julien the most uniform and orderly in its gravel formation, with just a border of clay at the entry to the appellation; St Estephe the most eccentric, with its clay and limestone pockets giving Merlot some of the minerality that it more usually expresses in Saint Emilion; Listrac and Moulis always trying to catch up with the big kids – flashes of brilliance with their clay and gravel, but brought down by the layer of sand that lies close to the surface. A tasting of four wines chosen by Boissenot puts this into perspective – grown on three different gravels, and one clay/limestone, all from the 2005 vintage (a useful one for would-be geologists because the harvest was healthy and ripe).

Wines to Try

Chateau Potensac AOC Médoc 2005 (clay-gravel over limestone)

A former Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnel, owned by Domaines Delon of Léoville Las Cases, the colour here is ruby red, not the young purple of en primeur, but a good medium intensity. Very open nose, not hugely complex but pretty, red fruits, black cherry, touch of coconut whiskylactone aromas and smoky oak. I have a touch of imbalance with the alcohol, but the tannins are firm, there is good freshness and you can feel the influence of the 75% Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend. A classic Medoc, medium persistency, a little abrupt on the finish, not overly generous, but elegant. Drink now.

Chateau Fourcas Dupré AOC Listrac-Médoc 2005 (Tertiary era gravels, with some sand)

The blend here is 50/50 Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot. Soft purple-ruby colour, beginning to lighten around the rim, with a touch of the russet, tile-red tertiary colours that will become more obvious over the coming years. Aromas also started to evolve, I get a touch of leather, animal, even a touch phenolic, but at the same time there are attractive autumnal fruits, with the impression of a well ripened harvest, not overly extracted. A little heat on the attack, but tannins well integrated, not rustic, not hugely persistency. Perhaps a little over-evolved for a really good 2005. Drink now.

Chateau du Tertre AOC Margaux 2005 (well-elevated outcrops of Tertiary era gravel)

With a blend of 20% Cabernet Franc, 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, du Tertre is on two of the highest gravel outcrops in the Margaux appellation, with excellent drainage. The colour a little different from the others; a medium intensity brown-ruby. The nose is welcoming, toasted, roast-coffee in style, but with a good fruit. Not too exuberant, a touch of vanilline, prunes, plums, there is a gourmet side to this, lightly spicy, leather, balsamic. Good complexity on the aftertaste, with silky tannins and cedar wood. It is beginning to open for me, maybe a little shorter than the Lagrange, but lots of pleasure. Just beginning to approach its drinking window.

Chateau Lagrange AOC St Julien 2005 (gunzien Quartenary gravel of varying sizes, with some areas of sand and clay)

Blend is 70% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, with a touch of Petit Verdot. The colour is the most intense of the four wines here, purple-red, medium-plus in intensity. Nose more closed than the others, you need to really roll it around the glass to open it up. Here have black cherries and black pepper spice. The oak is also evident, but less exuberant than with the du Tertre, much more linear. A touch almost of green pepper for me, the youngest-seeming of the wines tasted by far, the most strict. The Lagrange style is often virile, always takes a long time to age, and usually does so very well. Acidity, freshness, firm tannins, bilberries and blackcurrants, with a touch of crème Anglaise sweetness from the oak. Give until at least 2016 before drinking, perhaps even 2018 for it to start really opening up.

Columnist Introduction

Jane Anson is Bordeaux correspondent for Decanter, and has lived in the region since 2003. She is author of Bordeaux Legends, a history of the First Growth wines (October 2012 Editions de la Martiniere), the Bordeaux and Southwest France author of The Wine Opus and 1000 Great Wines That Won’t Cost A Fortune (both Dorling Kindersley, 2010 and 2011). Anson is contributing writer of the Michelin Green Guide to the Wine Regions of France (March 2010, Michelin Publications), and writes a monthly wine column for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she lived from 1994 to 1997. Accredited wine teacher at the Bordeaux Ecole du Vin, with a Masters in publishing from University College London.

Click here to read all articles by Jane Anson>>

- Follow us on Weibo @Decanter醇鉴 and Facebook

and Facebook for most recent news and updates -

for most recent news and updates -

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit