CH'NG Poh Tiong's column: Zuo Wang

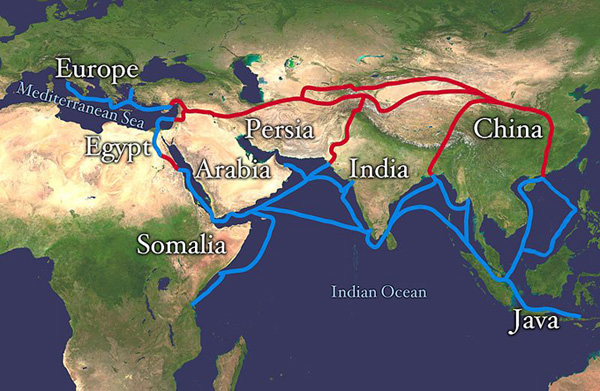

The ancient Chinese Silk Road is one of the most famous trading routes in world history.

The overland journey between China to the Mediterranean Sea cut across well-mapped roads, steep rocky paths and inhospitable dessert. As for the landscape, that ranged from accessible lowlands to difficult, even dangerous, mountainous terrain. Considering that journeys can last for months, even years, caravans would naturally want to avoid being trapped in freezing winter storms when crossing the highest points of the Silk Road.

Although trade went on in both directions (since it would be a lost trading opportunity if traders picking up silk from China came empty-handed when they arrived), it was really silk that the world wanted from the Chinese rather than the Chinese desiring things from the other direction (except perhaps for jade). Hence the name the Silk Road or Silk Route.

Evidence of silk has been discovered in China from 5,000 years ago. In fact, China was the first country to produce the light, lustrous fabric. The first time someone outside China saw silk was probably about 3,000 years ago.

Imagine that person who had only known rough and coarse fabric touching silk for the very first time. He or she would have wondered, “What on earth is this?”. And when that person drape it over the body and felt how soft it was, he or she would have thought the whole experience was magic rather than real-life.

China not only invented silk, it also had a monopoly on the cloth. And when the country decided to trade in it (particularly during the Han Dynasty 206 BCE–220 CE), silk immediately became the world’s most-sought after luxury item (way before Hermes, Chanel, Prada or Louis Vuitton were even born).

Imagine again if in today’s world there is a country – and no other - that produces cars. Everyone will then have to buy cars from that country. How incredibly wealthy that country would be. China was such a country more than two thousand years ago.

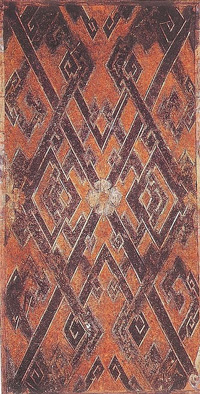

Mawangdui, Changsha,

Hunan province, China.

Of course while China had a monopoly on silk, it didn’t mean that everyone had to wear silk. There were other much heavier and thicker materials such as leather, wool, linen and cotton. Only the very wealthy could afford to wear silk, whether in China or those countries that imported silk from her. In fact, there was a time when only the emperor and his family could wear silk. No one else was allowed to do so. Before paper was invented in China, silk was also used for painting.

Two thousand years ago, a guest arriving at a dinner wearing silk would have been like someone today arriving in a Bentley or a Ferrari. You would instantly be recognised as someone who is very wealthy (unless the car was bought on a hire-purchase loan).

Apart from the overland Silk Road, there was also a maritime Silk Road. During the Ming Dynasty (1365-1644), the Yongle emperor (reigned 1402-24) initiated several expeditions. These were led by Admiral Zheng He (1371-1433) which traded with countries in the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, Red Sea and as far as the east coast of Africa.

With the passage of time, other countries discovered the secret to producing silk and China lost its once iron grip on the soft, smooth fabric. The Silk Road continued to be used for trading but its importance started to decline. The Silk Route finally became a thing of history when ships, trains and aeroplanes became a cheaper and faster mode of transportation.

In modern times, from about 20 years ago, another kind of ‘Silk Road’ has been created. It’s certainly not overland. Instead, the product is loaded onto ships and planes rather than camels. This traffic is nor from, but bound instead for China.

If 2,000 years ago everyone wanted silk from China, now everyone wants to sell to China, including Bordeaux wine. In less than 20 years, China has overtaken – in value and volume – the United States of America and the United Kingdom as the most important market for the wines of Bordeaux.

The good news is that it is not just for trophy wines such as Lafite-Rothschild, Chateau Margaux, Latour, Mouton-Rothschild or Chateau Haut-Brion. Chinese consumers are interested in Bordeaux wine across the whole price range. From the most humble, simple generic Bordeaux Rouge to exalted properties of the 1855 Medoc Classification and the ultra-rare properties of the Right Bank such as Petrus, Le Pin and Cheval Blanc, China is where Bordeaux clamours to be.

Since 2005, I have been organising a series of Masterclass tastings and dinners with some of Bordeaux’s finest wines. I selected them on the basis that they produce classic, elegant, intense wines. Not big blockbusters, overly-extracted, black wines that will knock our teeth out.

At the Masterclasses, we taste the same vintage of every participating chateau. This year, it’s the turn of 2009, one of the most expensive vintages on record.

The cities we will be visiting are Hangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing & Singapore.

The Masterclasses are free-of-charge but you have to register at wine@thewinereview.com.sg. The dinners are offered at practically cost price. The reason we do this is because we want as many wine lovers as possible to attend them. The proprietors/representatives of the chateaux will be in attendance at both the Masterclass tastings and dinners. It will be a great opportunity to interact with them. All are very friendly and have visited China many times. The dinner wines and vintages are:

Domaine de Chevalier White 1996

Domaine de Chevalier Red 1996

Chateau Leoville Barton 1999

Chateau Pichon Baron 2001

Chateau Petit Village 2000

Chateau Brane Cantenac 2000

Chateau Suduiraut 1999

Since the beginning, my Bordeaux friends and I have been committed to pairing their wines with our Chinese cuisine. We do so because they taste wonderful together and so because both the wines and the cuisine share a great heritage and history.

Three cheers for this ‘Silk Road of Wine’.

Event Details:

Masterclass>>

Dinner>>

Columnist Introduction

A lawyer by training, CH’NG Poh Tiong also holds a Postgraduate Certificate with Distinction in Chinese Art from the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. He is an Honorary Ambassador of TEFAF – The European Fine Art Fair – Maastricht. CH'NG works principally as a wine journalist and is publisher of The Wine Review, the oldest wine publication in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong and China since 1991.

Click here to read all articles by CH'NG Poh Tiong>>

- Follow us on Weibo @Decanter?? and Facebook

and Facebook for the latest news and updates -

for the latest news and updates -

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit