CH'NG Poh Tiong's column: Zuo Wang

The number ‘13’ is considered unlucky in Western culture.

It’s just a superstition but, whether we are easterners or westerners, most of us try to avoid superstitions for the simple reason we don’t like to tempt fate.

It does not mean we believe entirely in them but we tell ourselves, ‘Why take the unnecessary risk?’

That way, if we avoid the superstition and nothing happens, we think it is because we took the right precaution. On the other hand, if we didn’t and something actually happens, we end up regretting we did not pay the necessary attention to the superstition.

Back to the number ‘13’.

An English friend tells me that in his home, if 13 people turned up for dinner, they put an extra chair at the table. And then place a teddy bear on the seat so that now, there are 14 people for dinner.

I think it is such a silly yet ingenious and endearing idea.

Some Chinese people would, however, prefer to avoid 14 people at dinner because ‘4’ is a homophone for ‘death’. In Cantonese, ‘14’ would sound even worse because in that dialect, it’s ‘Sure to Die’.

On the other hand, we have no problem with 13. In fact, for Cantonese people, it’s wonderfully positive because ‘3’ is a homophone for ‘alive’.

Numbers are not just associated with superstition. They may offer us clues to hidden meanings.

In the classic ‘Water Margin’, there are 108 heroes.

The story is set in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Although there is no conclusive evidence as to the identity of the author (there may have been more than one), the fact there are 108 heroes suggests he is a Buddhist. The reason for this conclusion is because there are 108 prayer beads in the Buddhist mala.

For Chinese people, the numeral we are most obsessed with is ‘8’.

Whether in Cantonese or Putonghua it sounds just like ‘Prosperity’. And ‘28’ or ‘Easy to Prosper’ is the best. In fact, in auctions or sales of car numbers - whether in Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau or Mainland China- 28 is always the most expensive.

These days, whenever I see newly registered cars on the roads in Singapore with numbers such as ‘28’, ‘288’, ‘2828’ or ‘8888’, I find them to be in bad taste because such people are obsessed with money. It’s as if they are ‘advertising’ to the whole world that money is the most important thing in life.

When it comes to wine and their vintages, we cannot, of course, blame the innocent thing that it was born and harvested in, for example, 1928 or 1982. In fact, both are great years for champagne and Bordeaux.

But ever since China became such an important market, exporters have exploited the country’s obsession with the number 8.

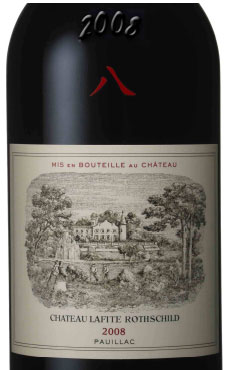

I am sure some of you will remember that for the 2008 vintage, Chateau Lafite-Rothschild actually added the Chinese character ‘8’ on the bottle.

That piece of news was actually first reported by decanter.com, the sister website of decanterchina.com, on 27 October 2010.

Simon Staples, then sales director at London merchant Berry Bros and Rudd (but now based in their Hong Kong office) said, ‘It’s gone bonkers, we sold 75 cases this morning. We literally cannot buy any more of it.’

Another English wine merchant, Farr Vintners, their Chairman and Owner Stephen Browett recorded the same knee-jerk reaction from Chinese demand.

‘This is a wine that we sold at £1,950 en primeur 18 months ago and it reached £9,000 recently. As a result of the announcement it has hit £10,000 a case and we are out of stock.’

If you were able to buy a case back in late October 2010, you would no doubt have congratulated yourself on your good fortune. And if you had resold it at an even higher price, you would have thought how lucky the number 8 truly is.

Here, though, is the reality if you hung on to the wine.

According to a report by United Kingdom company Liv-ex dated just two weeks ago on 8 May 2013, a case of Chateau Lafite 2008 is now worth only £6,425.

Far from being lucky, you would now be kicking yourself for having let the number ‘8’ seduced you into losing money.

There’s a figure in Chinese culture which is more of a concept rather than a number. This is ‘10,000’.

When China had emperors, subjects had to wish that they live ‘10,000 years’.

This was of course an illusion. It was just a way of wishing the emperor a long life. There was simply no reality to it whatsoever.

The emperor himself knew it was not humanly possible to live so long. So did the people – chancellor, ministers, generals, concubines and eunuchs – who had no choice but to wish him such unattainable longevity.

It’s a form of deception where everyone knew that as soon as they open their months they were already lying.

The emperor himself was, of course, the chief deceiver.

It wasn’t only in speech that such delusions were practised. In paintings too, the emperor had to appear physically bigger and taller. And some times, he would even look more handsome than in real life (before the days of photography and television, you could get away with this because not many people actually had the opportunity to see the emperor).

In the history of China, no emperor lived to his 100 birthday, let alone 10,000 years. If they were lucky, they died naturally (and hopefully not in captivity) while others were murdered in palace plots devised by their eunuchs, rival siblings or members of their own or extended families.

So, whether it is the number ‘8’, ‘28’, ‘888’ or ‘10,000’, treat all of them with the necessary disbelief even when you are hoping for the best. Don’t get carried away because otherwise you may end up losing money or something else that is even more precious.

If it is just wine that has gone down in price, at least you can still drink and enjoy the bottles. But if it’s Lafite 2008, I’m afraid it’s much too young. Try it in 2028.

Columnist Introduction

A lawyer by training, CH’NG Poh Tiong also holds a Postgraduate Certificate with Distinction in Chinese Art from the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. He is an Honorary Ambassador of TEFAF – The European Fine Art Fair – Maastricht. CH'NG works principally as a wine journalist and is publisher of The Wine Review, the oldest wine publication in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong and China since 1991.

Click here to read all articles by CH'NG Poh Tiong>>

- Follow us on Weibo @Decanter醇鉴 -

-

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit