Jefford on Monday

Peter Gago is Penfold’s chief winemaker: a dream job with, I suspect, many nightmarish moments. He clipped through London this September to show off the company’s 2015 releases around a month before they were officially unveiled -- in Shanghai. More of those in a minute.

Gago was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, emigrated to Austraila with his family aged six, and taught maths and chemistry before becoming a winemaker. We first talked when he was in charge of Seaview sparkling wines (probably not a dream job). I remember an intelligent, good-humoured, smiling interlocutor of astonishing articulacy. That, plus raw winemaking talent, propelled him with almost unseemly speed into shoes once filled by Max Schubert.

The good humour should have been ground out of him by his barely sane travel schedule and the relentless corporate struggle (“a battle a day”, he once confessed). Combining the honesty essential to a winemaker and the ‘optimism’ required to front sales and marketing endeavours would challenge anyone’s intelligence. Dealing with the wine world’s media egos must test articulacy to the limit. But there he was in September, still offering thoughtful answers to questions I’d barely formulated, and still smiling despite having been trounced for his honesty in admitting that the 2011 Grange could not be, and is not, the best vintage of this wine ever made.

Indeed Mr Vince Salpietro, manager of the Grand Cru wine shop in West Australia’s Perth, filmed himself last month pouring two bottles of Grange 2011 onto a cellar floor to make the point, reinforced in a print advertisement, that “The 2011 Grange is a very ordinary wine and they haven’t moved on pricing. ... It feels to me, if you’ll excuse the language, that Penfolds are taking the piss.” (The ad should do wonders for his allocation of the 2012.)

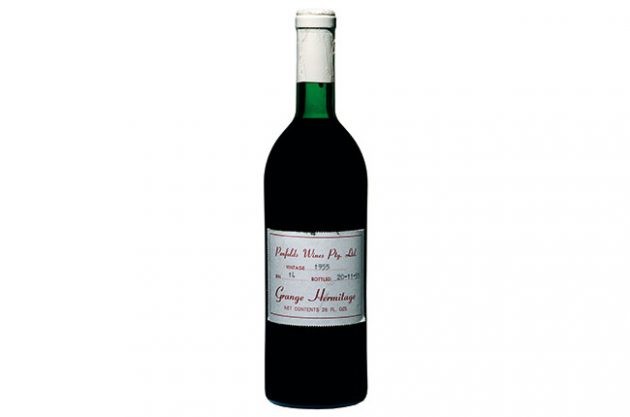

It’s strange to see Grange in a classic Bordeaux bind – but not illogical, as it has long functioned as Australia’s singular equivalent of a Bordeaux First Growth. Vintage fidelity is as intrinsic a part of the Grange premise as it would be for any Lafite or Latour – though more beguilingly so, it could be argued, since the cross-regional blending freedom this South Australian red allows itself gives its creators the chance to optimise a vintage, rather than simply make the best wine a large vineyard could turn out under the circumstances. The company hasn’t dropped a vintage yet.

2011, though, clipped the winemakers’ wings. Remember that, as the grapes which went to make this wine were limping towards ripeness, Australia was in the grip of the most significant La Niña event in its history: a cool summer with record rainfall over much of the country, provoking some of the biggest floods even elderly Australians could remember. It was only South Australia’s warm areas which could compete for inclusion: mostly northern Barossa, some McLaren Vale, a teaspoonful of Magill Estate in Adelaide. All Shiraz, too (it ripens earlier than Cabernet). ‘Relegating, relegating, relegating,’ was how Gago remembered the selection process, which left Penfolds with half its normal production of Grange. That, presumably, is the rationale for pricing 2011 on par with the points-laden 2010.

Is retailer Vince Salpietro’s torpedo (“a very ordinary wine”) on target? I don’t think so, though it could be argued that Gago’s generosity in showing it to UK palates alongside the extraordinary 1971 Grange and the classy 1991 Grange was courting trouble. Shortly afterwards, too, I tasted the 1986 with a friend in South Lanarkshire; notes for all four Granges are given below, plus further notes for most of the new releases.

The choice of Shanghai to launch the range (complete with specially commissioned film, narrated by Russell Crowe; live orchestra to perform the specially commissioned music, plus solo performance by pianist Li Quan; museum tour, hostesses, tuna belly, caviar…) underlines the fact that parent company Treasury has the burgeoning and potentially enormous China market in its sights. Penfolds’ emphasis on red wines, its overt wine hierarchy, the key role played by numbers in its branding, a helpful local nickname (‘Benfu’ – the ‘journey to wealth’), and the fact that it delivers intricate wine narratives with consistent and reliable sensual profiles makes it a perfect fit for eager, fast-learning Chinese drinkers at present. The land of his birth may see less of Gago in the years to come.

A Grange Quartet

Grange is a showy wine. It reminds me of a carnival or a fairground: lots going on both at ground level and up in the sky; full of noise and bright colour; something extraordinary to greet you wherever you peep inside the wine. In recent years, though, Peter Gago has added intricacy and finesse to the blends. The 2011 Grange doesn’t let the side down, in that it has the diagnostic excitement the Grange name triggers, and it’s vivid and concentrated. The fruit is less plump and swelling than in recent vintages, and the palate more edgy and crenellated; the flavours flirt with prunes and coffee. But it remains a remarkably concentrated, engaging and -- with due respect to Vince -- un-ordinary wine (91).

The 1991 Grange seems to be at a serene stage of evolution: refined, airy and unthrusting just now. On the palate, it’s pure, poised, sustained, long and elegant, with head-turning curranty fruit and a fine-stranded textural mane: a Margaux-like Grange. Just five per cent Cabernet, but you might easily guess it was more (95).

The 1986 Grange was a bigger beast, despite the extra years, with splendid and very Australian aromas: resin, mint and eucalyptus drifting over sweet, settling fruits and warm cereal grains. Rich and thick yet not particularly tannic; in drinking, the sweetness seemed to win out over the other flavours (93).

The 1971 Grange, finally, was extraordinary in all its parts. Deeply coloured, with a great engine of aroma that surges out of the glass like an army: an assault of rosemary, crushed pine needles, pressed mint, hammered caramels and apothecary essences. On the palate, it has astonishing concentration and ripeness, and unbridled force and thrust, its salty-sweet, rooty fruit clad with that same repertoire of hot forest and herbal-medicine tones (98). That such a wine-object could emerge so ripely and so resonantly from its season clad in just 12.3% is sensual proof of just how much our planet has changed in the last half-century. (I don’t think biodynamics in our current climate will ever duplicate this, no matter what believers claim.)

Penfolds White Wines

I’m a big fan of Yattarna, though I hope it doesn’t get any slimmer than the 2013 Yattarna is: a discreet, enigmatic Corton-Charlemagne style of aroma, then a ballet of green fruit on the palate (92). More time is definitely needed for this fine Tasmanian Chardonnay (plus 10 per cent Adelaide Hills). Almost as good on the day for me, though much less expensive, was the 2014 Bin 311 Tumbarumba Chardonnay: woolly scents and lively, vinous and pithy on the palate. Petite yet ripe, and very moreish; a great ringer to shove in a blind tasting of decent white Burgundy (91). The 2014 Reserve Bin A (from the Adelaide Hills) is a more flamboyant Chardonnay style: bright, elemental, a little bit tangy (88), while the beautiful Bin 51 Eden Valley Riesling manages to be both blossomy and crystalline, with a brisk, breezy palate (90).

Penfolds Red Wines

The weakest wines in this generally impressive range for me were the oddly sweet, kinky, lush yet unpleasantly acidic 2013 Magill Estate Shiraz (84) and the florid 2014 Cellar Reserve Pinot Noir, a showboat Adelaide Hills Pinot spilling grenadine and trembly blackberry in its wake (86). There’s great value, by contrast, from the 2013 Bin 138 Barossa Valley Shiraz Grenache Mataro: a nose of gravy, earth and fig, and mouthfilling, broad, friendly, ‘give us a wave, Mum’ flavours (89).

In the battle of the 28s, my vote’s for Kalimna (a brand name not a vineyard name here, remember: the wine contains fruit from Langhorne Creek, Padthaway and McLaren Vale as well as the Barossa): the 2013 Bin 28 Shiraz smells savoury, fat and earthy, while its flavours are classy, calm and impeccably organized, lifted by a finishing soft wealth (93). The 2013 Bin 128 Coonawarra Shiraz, by contrast, is a limpidly fruity wine, smooth, classy and high-toned (89).

What of the grandees? I loved the complex, secondary aromas of the 2012 St Henri (herbs, plant juices, unlit tobacco leaf), but found the flavour stern: lots of acidity, very little tannin, and a very gently fleshed palate, even in its youth (89). The 2013 Bin 407 Cabernet Sauvignon is commanding, showy and sweet (88), while I also struggle with the palate sweetness of the 2013 Bin 707 Cabernet Sauvignon: evidently classy raw materials, but the new American oak ageing is very dominant (Peter Gago’s own notes, not unreasonably, touch on marmalade, citrus, sundried tomato and Irish fruit cake) (90). Mix Cabernet with Shiraz, take away most of the new oak, and suddenly you have what is for me a much more interesting wine, the 2013 Bin 389 Cabernet Shiraz: infinitely subtler aromatic complexity, and deep, Australian flavours of true profundity: forest edge leaf litter, saline red fruits, plant sap density and some serious tannin (94).

Finally, three pure Barossans to finish. The 2013 Cellar Reserve Sangiovese (now, happily, available internationally via global travel retailers) has ‘no fining, no correction, no new oak and just a squirt of CO2’ according to Gago; it also gets five weeks on its skins. Given this, I’m amazed that it’s as un-tannic as it is, but the fruit has fine innate complexity and some of the austerity the variety exhibits back in Tuscany (91). The 2013 Bin 50 Marananga Shiraz is the most voluptuously attractive wine in the whole range, but with great fruit purity, too, though these charms ride out on their own; there isn’t a lot of structure and extract behind them, though there’s plenty of acidity (90). More textural complexity and depth is apparent in the 2013 RWT, and the fruit here has unrivalled elegance and spicy finesse (the 2013 Bin 28 Kalimna is fatter, more savoury and meatier). The RWT is also the most aromatically complex of the 2013 Shiraz wines (92).

Columnist Introduction

Andrew Jefford is a columnist for both Decanter magazine and www.decanter.com, Jefford has been writing and broadcasting about wine (as well as food, whisky, travel and perfume) since the 1980s, winning many awards – the latest for his work as a columnist. After 15 months as a senior research fellow at Adelaide University between 2009 and 2010, Andrew is currently writing a book on Australia's wine landscape and terroirs. He lives in the Languedoc, on the frontier between the Grès de Montpellier and Pic St Loup zones.

Click here to read all articles by Andrew Jefford>>

- Follow us on Weibo@Decanter醇鉴 for the latest news and updates -

for the latest news and updates -

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit