Some areas of Chile and Argentina are experiencing changes in the frequency and severity of weather extremes. While many winemaking regions struggle to adapt, there are some visionary producers who see it as an opportunity to explore. Amanda Barnes investigates.

The wine map is undeniably changing. The worldwide phenomenon of climate change is creating new, once-unimaginable wine regions, while at the same time dismantling others in its path. The oxymoron is, of course, that it poses both distressing risk and thrilling opportunity for winemakers.

Belonging to a hemisphere with more water than land, global warming in South America is relatively gradual. ‘Global weirding’, however, has been a bit more dramatic, as the last two vintages testify. 2016’s El Niño, nicknamed Godzilla, caused snow in Elqui, flooding in the Atacama desert and one of Mendoza’s wettest vintages on record, while the extreme heat of early 2017 led to the worst forest fires in Chile’s history and electrical storms setting Argentina’s Pampa ablaze. On the Atlantic coast, hurricanes are becoming an almost annual occurrence and in 2016 Uruguay experienced its first tornado.

The bad news is that extreme weather events will likely become the norm. However, climate change brings greater concerns: ‘Water scarcity is the biggest threat of climate change,’ predicts Dr Fernando Santibáñez, director of Chile’s Agriculture Department, Agrimed. ‘The other problems – like increased variability and extreme events of intense rains, wind and hail – are secondary.’

Action plans are underway in Chile to prepare for the probable warmer, drier future. Water salinity, vineyard UV radiation and smoke taint detection are today’s top priorities at Concha y Toro’s US$5 million research centre; and Wines of Chile is mapping out a 40-year viability study into both existing and potential wine regions based on climate change predictions.

Argentina’s industrial initiatives are more timid, as short-term economic stability pulls rank, but wine producers are already adapting their viticulture in response to the changing climate. In both countries we can get an idea of what the future might taste like and the direction their wine regions are heading.

The coast

One of Chile’s greatest assets is its long, cool Pacific coastline. It may be too cold to swim, but the chilly temperatures should safeguard maritime wine regions. ‘The ocean currents will become more intense which, paradoxically, will make the shallow waters colder,’ explains Dr Santibáñez. ‘It should neutralise the effect of global warming on Chile’s coastal regions.’

First planted in the 1980s, Casablanca and neighbouring San Antonio remain the centre of Chile’s coastal wine scene. But coastal regions are emerging from Bío Bío up to Huasco, where even the Atacama desert is no match for the cold Humboldt Current. ‘Our Atacama vineyard is so close to the sea, it’s a cool coastal desert,’ says Tara winemaker Felipe Tosso. ‘It’s cooler than parts of Casablanca.’

Sauvignon Blanc was once the mainstay of coastal regions, but today there’s ample variety. Vineyards can ripen fruity Grenache, but stay cool enough for razor-sharp Riesling, as proves Chile’s most seafaring producer, Casa Marin, just two miles from the sea.

The only limit in Chile’s coastal regions is the shortage and expense of fresh water. In Limarí several producers have recently abandoned vineyards. ‘People planted more than the valley could support,’ says Maycas del Limarí winemaker Marcelo Papa, who only has half the estate in production, to give him some leeway with the limited water allowance. ‘I’m confident about the future of Limarí, and fortunately coastal vineyards consume 25% less water (because they transpire less).’

In Argentina, maritime wines are a new phenomenon. Peñaflor’s Costa y Pampa pioneered a new wine region on the coast in Chapadmalal, Buenos Aires, closer to the Atlantic-facing vineyards of Uruguay than the heartland of Mendoza. ‘We have to leave our comfort zone and look for new productive regions with cooler climates,’ says viticulturist Marcelo Belmonte. ‘Maritime viticulture will develop more in the future.’ Plans are afoot to double its vineyards, setting an exciting benchmark for coastal Argentinian wine.

The south

‘Chile’s wine regions are expanding south,’ says Fernando Almeda at Miguel Torres Chile, a company that has recently invested more than US$7m in 780ha (hectares) between Maule and Itata. The investment includes the revamping of old varieties such as País into fresh sparkling rosé and crunchy, carbonicmaceration reds, and planting new vineyards like Empedrado, where the company makes a handsome Pinot Noir on schist terraces.

Chile’s new horizon though, is even further south – towards Patagonia. Viña Aquitania was the pioneer of Chile’s deep south, planting in Malleco in 1995. ‘People thought we were crazy when we planted here,’ laughs winemaker Felipe de Solminihac, ‘but since then Chile has developed from south to north and coast to mountains, looking for cool conditions. We planted here before Leyda even existed!’

For many years Aquitania was the sole producer in Malleco, but today there are more than 30 producers there, seeking out the chiselled acidity and delicate aromas this cooler, wetter region offers.

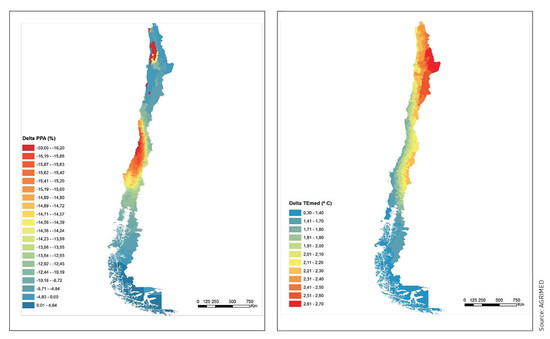

As temperatures increase and rainfall dwindles (see diagrams above), Patagonian wine regions aren’t so marginal anymore. Vineyards are thriving deeper south in Villarrica, Osorno and towards Puerto Montt. Furthest south of all is Undurraga’s Chile Chico vineyard, on the 46th parallel, just a few miles from Argentina’s southernmost vineyard in Los Antiguos.

Both are still in the experimental stage, but Undurraga’s winemaker Rafael Urrejola is hopeful: ‘It’s definitely feasible and interesting, but it takes time to establish a new viticultural region.’ When they do, it will be the southernmost wine region in the world.

Increasing altitude

Argentina’s original high-altitude wine region is Salta, first planted in the mid-1600s, where vineyards today reach 3,000m above sea level. Unaware of climate change, intuition guided them – and altitude effectively mitigated the intense heat of life on the 26th parallel.

As temperatures crept up all over Argentina, so did vineyards. ‘My father planted vineyards so far west towards the Andes and so high that people told him his grapes would never ripen,’ recalls Laura Catena, whose father Nicolás planted Mendoza’s first high-altitude vineyard in Gualtallary (1,500m) in the 1990s.

The difference is palpable. Mendoza’s lower altitude wine regions, such as Lunlunta, are considered Winkler Region IV (as warm as the southern Rhône), while Alto Gualtallary is Winkler Region I, equivalent to the cool climate of Champagne.

The hunt for vineyards in Mendoza is reaching new heights. ‘Argentina’s challenge is to look for cooler regions,’ explains winemaker Matías Michelini, whose latest Uco Valley adventure is Pinot Noir and Chardonnay planted at 2,000m. ‘Mendoza is a desert with many days of sunshine. To make fresher, more elegant wines, we have to look higher.’

Michelini joins other pioneers of new altitude regions including Alejandro Sejanovich in Uspallata (2,040m) in Argentina, and Tabalí (1,850m) and Viñedos de Alcohuaz (2,200m) in Chile’s Limarí and Elqui valleys.

The increasing altitude doesn’t just reflect climate change, but also the new personality of South American wines. ‘Today we are moving the limits, looking for a different style, a different expression,’ explains winemaker Sebastián Zuccardi, whose family winery has moved from Maipú to the Uco Valley over the past decade. ‘This has been driven by a focus on new unexplored regions, more than by climate change.’

The past

Looking at old records, and the living records of old vines, holds the key to the future, according to Santa Carolina winemaker Andrés Caballero: ‘Chile still has a great diversity of pre-phylloxera material, which can help us a lot in the future.’ Over the last seven years, its Heritage Block project has focused on identifying the best-adapted genetic material for changing climate conditions, and returned to historic winemaking techniques.

The renaissance of historic winemaking traditions is widespread in Chile and Argentina, with winemakers such as Louis- Antoine Luyt, Marcelo Retamal and Matías Michelini leading the way in orange wines, natural winemaking and revaluing historic vessels. However, it is the viticultural heritage that might offer the best counter-balance to the effects of climate change. ‘The real wine of the world is dry-farmed,’ surmises Retamal.

‘With ungrafted, 120-year-old vines, Chile has a great opportunity to produce world-class wine with real emotion and heritage.’

As with any future planning, sustainability is key – and southern Chile’s winemaking patrimony is under threat. ‘If these producers only sell grapes, they are in a really weak position… All the fuss about Carignan, and demand for grapes, actually killed Cauquenes as a winemaking region,’ says Leonardo Erazo, whose Viñateros Bravos project empowers Itata vignerons to make their own wines through a profit-sharing model. The winemaking legacy of South America’s oldest viticultural regions is just as valuable, and relevant for the future, as the old bush vines.

Bush vines, or head-trained vines, were the first type of plantings in South America, but both Chile and Argentina gradually converted to a vine system mimicking Bordeaux – leaving grapes fully exposed to the sun. That system works well in rainy, cooler climates, but in the sunny, warm climates of Chile and Argentina the grapes more frequently get sunburnt, resulting in cooked flavours.

Today many viticulturists are returning to shadier, sprawling canopies and head-trained vines, as planted by Montes in Chile, which has been implementing a system of dry-farming in Colchagua over the last decade. ‘We have found that Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Carmenère have adapted well to no irrigation,’ explains Aurelio Montes from the company’s Apalta vineyards, where some neighbouring properties are also trialling similar projects.

Uco Valley viticulturist Edgardo del Popolo reignited interest in bush vines by planting Doña Paula’s Gualtallary vineyard in 2005, which now produces its dark and textural bush-vine Alluvia Malbec. He has consequently planted several more dryfarmed vineyards in Uco, including his own head-trained PerSe vineyard at 1,500m.

‘Water is limited in Mendoza,’ del Popolo says, ‘so dry farming is more sustainable for the future. The combination of snow at this altitude and the water-holding capacity of limestone makes dry-farming possible.’

It isn’t always possible, but preparing for less water is paramount, according to ‘climate change and wine-growing terroirs’ author and climatologist Hervé Quénol: ‘The problem is that most of Argentina’s and Chile’s vineyards can’t exist without irrigation – it’s already extreme viticulture. As water levels decrease, the conflict between population and viticulture will increase.’

Mediterranean varieties

Although the Bordeaux varieties Cabernet Sauvignon and Malbec remain kingpins of Chile and Argentina respectively, the last few years have seen the arrival, and return, of Mediterranean varieties to the Southern Cone.

Apt for the rising temperatures and drier conditions, these varieties may be best suited to climate-change patterns. ‘Global warming will see increasing hours of sunshine, greater frequency of very hot days, and decreasing cool periods – all of which will shorten the phenological stages of the grapes,’ explains Martín Cavagnaro from Mendoza’s Climate Investigation Department.

While some old-vine Grenache and Mourvèdre vineyards remain in the warmer, eastern regions of Mendoza, the Uco Valley has become the new home for these Mediterranean varieties, with several producers embracing Grenache in particular.

US cardiologist and vigneron Dr Madaiah Revana conceived Argentina’s first GSM blend after spotting similarities between the rocky soils and ‘copious sunshine, arid weather and warm climate’ of both the Uco Valley and Châteauneuf-du-Pape in France. Today his floral, peppery and juicy Luminoso GSM is a sell-out through his Corazón del Sol wine club.

Chile is seeing a broader boom in Mediterranean varieties. While Syrah has long been a favourite across the country, today it’s Grenache, Mourvèdre, Cinsault and Carignan stepping into focus. ‘There is great potential for Chile to make big, juicy Grenache wines,’ says Felipe Tosso. ‘Chile is a sunny country and these Mediterranean grape varieties work really well here.’

As the climate changes and extreme weather events become commonplace, having an assortment of grape varieties to choose from will undoubtedly be a handy tool for the winemaker. It isn’t just red blends that are having their day in the sun, but also exotic whites such as Viña Alicia’s Tiara, a structured yet fresh blend of Riesling, Albariño and Savagnin from Lunlunta, Mendoza. There is a growing tribe of Argentinian and Chilean producers creating an exciting upsurge of premium white blends.

The future

The introduction of a more diverse selection of grape varieties doesn’t by any means spell an end to South America’s traditional wines – but it does show a broadening mindset. ‘I think, more than climate change, we are seeing an attitude change,’ philosophises PerSe winemaker David Bonomi. ‘And that’s an important thing as we face this new chapter.’

Some producers will, inevitably, bury their heads in the sand when it comes to change. But today there is a growing and dynamic community of winemakers steering Chile and Argentina forward. They are more attentive to their vineyards than ever before, and are thoughtfully interpreting the nuances of nature and their inherited, varied South American terroirs.

Amanda Barnes is a wine and travel writer from England, who has been based in South America since 2009 .

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit