It would be hard to describe Dijon as a big city. Around 150,000 people live downtown, and its half-timbered medieval houses give it the appearance of a small village that has been swelled by the addition of a few historic buildings such as Porte Guillaume and the gorgeous Dijon cathedral. The airport is so small that it currently operates on a year-to-year basis, struggling to get enough flights to justify its existence.

and adapted under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Unported licence.

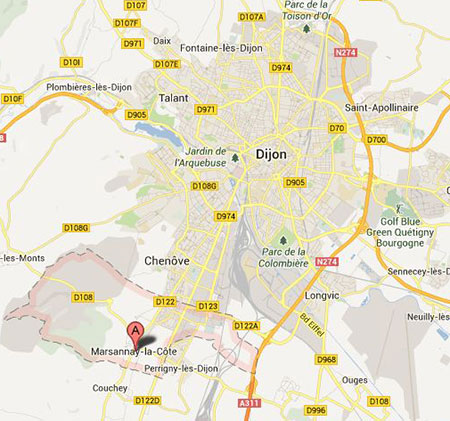

But ask the people of Marsannay whether Dijon is a big city, and you’ll get a very different response. This is the first wine village along Burgundy’s Côtes de Nuits as you head out of Dijon on the N274, and as such its vines are under threat from town planners looking to expand outwards. Issues of succession, and rising values of constructible land, mean vines close to city limits are more vulnerable than they should be all over France, and here it’s no different.

The winemakers are even in direct conflict with their own mayor, who is an enthusiastic supporter of building houses. The next door village of Chenôve, almost part of Dijon suburbs, had a full 300 hectares of vines in 1900 but Dijon and its railway line has cut that right down to 65 hectares today, with just 20 producers harvesting the grapes, and just three with their wineries within the village.

'In Marsannay, we have lost 100 hectares in 40 years to urbanisation, and regained just 30 hectares through replanting,' says Bruno Clair, president of the local Syndicate Viticole, and owner of Domaine Bruno Clair.

In 2011, winemakers took the local government to court in Dijon to overturn expansion plans that would have meant pulling up local vines, and they won. But they have another fight on their hands for the wines that is in many ways more intractable.

Ask why, and many locals will tell you that Marsannay was for many years the forgotten village of the Côtes de Nuits. Most will say that it only had itself to blame. What is certain is that for a long time it was known for its rosé wines instead of its reds – and more damagingly for its use of the gamay grape – today the emblem of Beaujolais, to the south of the region – instead of pinot noir.

Burgundy is so defined by pinot noir that it can be hard to believe that there was ever a fight between which grape would be best suited to the local terroir; pinot or gamay. But where pinot is a tricky, maddeningly elusive grape to get right, gamay offers a higher yield and earlier-ripening fruit, making it less vintage dependent. Many producers in the Middle Ages wanted to promote it, but the monks, together with the Duke who governed Burgundy at the time, ruled that growers risked fines and even prison for planting gamay.

After the French Revolution, with the demise of the church, some winemakers in Marsannay began planting gamay again, and found huge local success with their inexpensive, easy-to-drink wine. Marsannay became one of the wealthiest villages along the Côtes (the fine church standing almost opposite Domaine Bruno Clair attests to its success). ‘It was an accident of history, and made many producers wealthy, but it destroyed our image,’ says Clair. The arrival of Phylloxera destroyed great swatches of vineyards in Burgundy as it did across Europe, but after the crisis Marsannay, along with Chenôve and another neighbouring village Couchey, started once again planting gamay.

‘It offered a financial lifeline after Phylloxera, and then the 1929 crash, but this time,’ says Philippe Brun, longtime cellar master at Bruno Clair, ‘the world had moved on. Railways were bringing good-quality cheap wine from all over France, and the wine from here was to lose its market. But the producers were stubborn and still sure that Marsannay’s fame would be enough to carry it through. So when the appellation rules were created in the 1920s and 1930s, and Gevrey, Morey, Vosne and the other Côtes de Nuits villages signed up, Marsannay refused to do so, and was left behind’. The local winemakers were able to bottle under the generic AOC Bourgogne label, but not a more prestigious village appellation because gamay was not recognised as a quality Burgundy variety.

It was Clair’s grandfather who first made the move back towards planting pinot. He put his first vines in the ground – although used them for rosé – back in 1919. Quality plantings of pinot grew piece by piece over the next decades, and winemakers began pressing to overturn the mistaken decision of the 1930s.

provided by BIVB / GAUDILLERE TH.

It took until 1987 for Marsannay to be finally recognised as a village AOC (the only one to produce white, red and rosé), but still has none of the higher level Premier Cru vines. Local growers are convinced its terroir deserves the accolade, and a request has been made to the INAO, the French body that governs appellation rules, for a full 30% of its vineyard area to become Premier Cru.

Bruno Clair is among them, and has registered a request for his Marsannay Les Langeroies plot to become Premier Cru, with 90 year old vines planted at 10,000 per hectare. These were the first plots in the village replanted after the First World War, making a structured, fleshy wine bottled without filtering or fining.

‘We worry that the village has asked for too many plots to become Premier Cru. We believe that there are two climats - Les Langeroies and Clos des Roys - that are of unquestionable quality, that we fully hope to see recognised in the next few years. But we worry that arguments over the others will delay the application.’

Domaine Bruno Clair still makes a rosé from its young Marsannay vines. Made from a relatively long three day maceration of juice and skins, a typical Marsannay rosé is more structured that a rosé from southern France would be, and represents around 10% of the village’s overall production. Clair also makes several white wines – but as with most of his neighbours, is best known today for his reds. The estate has three reds from Marsannay, including Les Langeroies, and a good 18 others from around the region. The most prestigious are Chambertin Clos de Beze and Morey Saint Denis Bonnes Mares, where the vines are located right next door to Clos des Tarts, just on the far side of the famous wall.

‘Yes, we have good neighbours everywhere,’ agrees Clair with a self-deprecatory shrug. ‘But there will always be something about Marsannay for me. My grandfather moved here because he fell in love with a local girl, and I hope I can honour his memory.'

Columnist Introduction

Jane Anson is Bordeaux correspondent for Decanter, and has lived in the region since 2003. She is author of Bordeaux Legends, a history of the First Growth wines (October 2012 Editions de la Martiniere), the Bordeaux and Southwest France author of The Wine Opus and 1000 Great Wines That Won’t Cost A Fortune (both Dorling Kindersley, 2010 and 2011). Anson is contributing writer of the Michelin Green Guide to the Wine Regions of France (March 2010, Michelin Publications), and writes a monthly wine column for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she lived from 1994 to 1997. Accredited wine teacher at the Bordeaux Ecole du Vin, with a Masters in publishing from University College London.

Click here to read all articles by Jane Anson>>

- Follow us on Weibo @Decanter醇鉴 and Facebook

and Facebook for most recent news and updates -

for most recent news and updates -

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit