Andrew Jefford explores the perception of bitter flavours in wine....

Unpleasantly bitter and sour: that’s how new drinkers tend to find their first glass of red wine. Since most of us reach wine via soft drinks and fruit juices, we’re used to acidity: the strangeness of red wine is that it comes unaccompanied by any balancing sweetness. Semi-sweet wines provide an access route – and it’s not long before we come to appreciate ‘dry’ acidity, especially with food.

Bitterness is more intriguing. In evolutionary terms, we have only recently ceased being hunter-gathering omnivores, and bitter flavours were a warning signal that plants or animal parts might contain toxins. A sensitivity to the bitterness of the anti-thyroid drug propylthiouracil or PROP was identified (by psychologist Linda Bartoshuk in 1991) as the key test for distinguishing so-called ‘supertasters’ from the rest of the population; such individuals are also said to find the taste of cabbage or broccoli unpleasantly bitter.

They would struggle to like red wine. But, out in the primeval forests, they might have survived long enough to reproduce. The science of taste sensitivity has moved on since 1991, and differing sensitivities to substances including salt, citric acid, quinine and sucrose suggest that ‘supertasting’ is a complex picture. It’s not necessarily a winetasting advantage, by the way, since it may simply result in extreme pickiness.

What interests me, though, is the ability to override such sensitivities. PROP does taste bitter to me, given the standard test – yet I was a strange child who, when asked by indulgent strangers what my favourite food was, used to reply ‘Savoy cabbage’ (it helped that my mother never overcooked it). I drink copious quantities of black and green tea daily; I adore intensely hopped bitter ales and ‘peppery’ olive oil. A ristretto, in Italy, is a treat.

Tastes can be acquired. Indeed the ubiquity with which coffee, beer and bitter-sweet aperitifs and cocktails (think of Campari, or gin and tonic) are enjoyed by people around the world suggests that modern humans relish ‘dangerous’ bitter flavours. It’s a kind of cultural appurtenance.

Those flavours might also, paradoxically, do us good. ‘Tonic’ water (note the name) contains quinine, an anti-malarial, and at least some of the bitterness of tea and of wine derives from the tannins present in the leaves and stalks of the tea plant Camellia sinensis and the fruit skins and stems of Vitis vinifera. Plants produce tannins to dissuade predators from destroying them, so they are meant to taste unpleasant. But studies have shown that tannins can be anti-carcinogenic and are a useful antioxidative, as well as having the ability to accelerate blood clotting, reduce blood pressure and reduce serum lipid levels.

They also have preservative, anti-microbial properties – which might be why they found their way into grape skins. (Nature intended grapes to be eaten by birds, who don’t taste much anyway: parrots have just 400 taste buds, whereas humans have 9,000 or more.)

My contention, then, is that wine drinkers come to understand that bitter flavours in wine are in some sense tonic, since they are associated with some of the health-bringing substances which wine, and particularly red wine, contains. ‘Bitter’, though, is a wildly unsatisfying term in wine-tasting terminology (as is ‘acid’), since it is descriptive only in the most primitive sense. Any kind of extraneous or ‘chemical’ bitterness in wine is repellent.

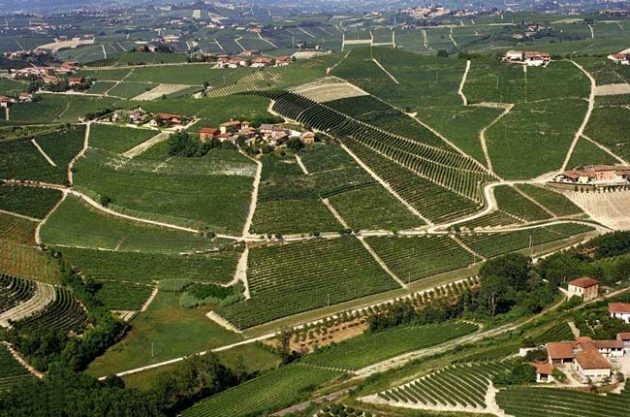

This, though, has nothing to do with the rich, affirmative bitterness which is a feature not merely of tannic red wines such as Barolo, Barbaresco, Bordeaux, Madiran, Bandol, Napa Cabernet, Bekaa Valley reds and others; but also of less tannic reds whose flavour profile includes a bitter component. These include most red wines from the Veneto and the Languedoc – that herbal ‘garrigue’ character, careful tasters will note, is a distinctively nuanced bitterness. What matters is that the bitter flavours themselves should be saturated and informed with other flavours – not naked and uncovered. The same thing applies to acidity in wine, which is why additions are usually a mistake. Richness is all.

Translated by ICY

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit