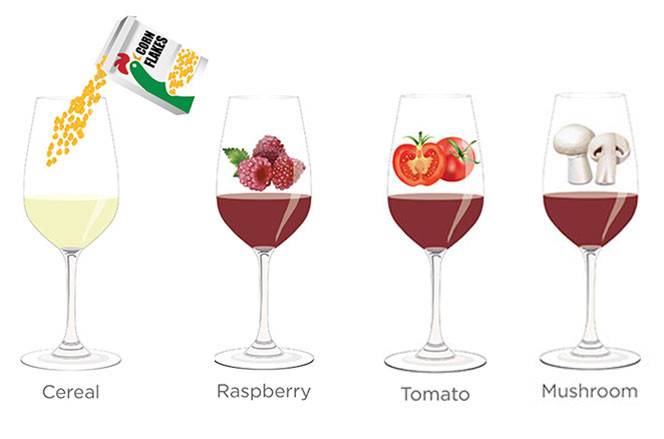

Cereal

Forget your morning bowl of coco pops and froot loops; in the wine lexicon, ‘cereal’ usually refers to the flavour profile of a basic range of grains like wheat, oats, maize and rye.

Cereal aromas are most common in non-fruit forward white wines and can be an indicator of maturity, as well as oak or yeast influences. Oak influences can be gained from the wine spending some time in contact with oak barrels, chips or staves, whereas yeast influences can be brought about through winemaking practices like stirring the lees (bâtonnage), or resting the wine on its lees (sur lie).

In this way, cereal is comparable with natural savoury-sweet aromas like honey and hay, which are also a sign of age and complexity in certain white wines, such as oak-aged Chardonnays.

For example, cereal notes of ‘savoury oatmeal’ feature in Domaine Jean-Louis Chavy, Berry Bros & Rudd Puligny Montrachet 2014, alongside cashew and chalk.

Sumaridge’s Chardonnay 2010 from Hemel-En-Aarde in South Africa is from a different hemisphere, but made in a similar style and also boasts savoury oatmeal flavours, enriched with layers of butter and pear.

Australian oaked Chardonnays, such as those made in Margaret River, may also have cereal hints, such as Hay Shed Hill, Wilyabrup 2012, praised by our experts for its ‘quiet notes of cereal grain’ with a ‘touch of brioche’.

You may also find cereal oaty notes in some sweet white wines, such as Château Doisy-Daëne 2013 from Barsac, noted for its ‘well-integrated oak’, resulting in undertones of ‘honey and oat’.

Raspberry

One of the tartest red fruits, raspberry has a distinctive flavour and aroma that’s relished in desserts and confectionery. Raspberries are genetically part of the rose family, alongside other soft hedgerow fruits like blackberries and loganberries (blackberry-raspberry hybrids).

In the wine lexicon, raspberry part of the red fruit category — at the tartest end of the spectrum, next to cranberry. Although some notes may contain ‘sour raspberry’, ‘tart’ is a more specific adjective, relating to their acidic yet sweet, fruity nature.

Given these characteristics, it’s more commonly detected as a primary aroma in ripe and fruit-forward red wines with medium to high acidity.

Many wines from around the world fit this description, but some typical grape varieties include Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc, Gamay and Tempranillo and Italian grapes like Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Barbera and Primitivo.

SEE: Collin Bourisset, Fleurie, Beaujolais 2015 | Tolpuddle Vineyard, Pinot Noir, Coal River Valley, Tasmania 2014 | E Pira and Figli, Cannubi 2006 | Bodegas Muriel, Taste the Difference Vinedos Barrihuelo Crianza, Rioja 2012

Lots of rosé wines typically have red fruit flavours and prominent acidity too, like Sacha Lichine, Single Blend Rosé 2016 from Languedoc-Roussillon. Or Graham Beck, Brut Rosé — a non-vintage sparkling wine from South Africa’s Western Cape, which combines ‘vibrant raspberry acidity’ with a leesy ‘brioche finish’.

You may see ‘raspberry jam’ in tasting notes, and this suggests the wine has more condensed raspberry tones; because jam making involves the addition of heat and sugar, which intensifies sweet and fruity flavours.

For example, Bersano, Sanguigna, Barbera 2011 from Piedmont is noted for its raspberry jam aromas, as a result of its ‘vivacious acidity’, plus intense and lingering sweet red fruit flavours.

Tomato

Tomato is one of the less common tasting notes, but nevertheless it has its place in the wine lexicon — among vegetal notes like green bell pepper (capsicum) and potato.

Tomato, green bell pepper and potato may appear to have little in common, but they all belong to the nightshade family and contain pyrazines — the chemical compound behind their sharply herbaceous aroma.

NOTE: When it comes to describing wine, tomato notes are commonly manifested as ‘green tomato’ or ‘tomato leaf’ — to highlight its herbaceous character, rather than the rich and sweet flavours of red ripe or cooked tomatoes.

A form of pyrazine (methoxypyrazine, to be exact) is found on the skins of grapes, which can heavily influence the flavour profile of resultant wines if the fruit is unable to ripen fully.

This can be particularly noticeable in Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Carménère wines, especially from cooler climate regions.

SEE: Masseto, Bolgheri, Tuscany 2006 | Robert Mondavi, To Kalon Vineyard Reserve, Oakville, Napa Valley 2012 | Château Tour Haut-Caussan, Médoc, Bordeaux 2010

Given time, this green tomato/tomato leaf character may evolve into complex notes such as cigar box, but it may never reach its full potential if the tannins were too undeveloped at the time of harvesting.

Herbaceous tomato notes can be desirable, such as in cool climate Sauvignon Blancs from Marlborough in New Zealand. For example Konrad’s Hole in the Water Sauvignon Blanc 2016, where tomato leaf and capsicum complement its citrus and green fruit character.

Sources: Decanter.com, Foodwise by Wendy E. Cook

Mushroom

Notice something fungi going on with your wine? Mushroom usually appears as a tertiary aroma, formed during the ageing process. Its flavour profile is associated with other earthy notes, such as forest floor (aka sous bois) and leather. These can develop in mature Pinot Noir wines, such as Marchand & Burch, Mount Barrow Pinot Noir 2013, where tertiary mushroom aromas overlay primary floral and red fruit notes.

Mushroom may also appear in aged Nebbiolo wines, such as those made in Barolo. In a similar way, red fruit and floral notes can become intertwined with earthy flavours and aromas, including leather, liquorice and mushroom. Premium, aged red Rioja wines and Sangiovese made in Brunello di Montalcino can display this effect too, although often with some spicy hints thrown in.

SEE: E Pira and Figli, Cannubi 2006 | Beronia, Reserva, Rioja Alta 2007 | Il Marroneto, Madonna delle Grazie, Brunello di Montalcino 2012

In the wine lexicon, mushrooms are in the fresh vegetal category, alongside notes like asparagus, green pepper and black olive. However, fresh mushrooms have a very different character to cooked mushrooms, which are associated with the so-called fifth taste, umami.

To understand the difference, find a fresh mushroom and take in its smell and flavour. Gently microwave your mushroom, and observe how its flavours and aromas alter.

The umami flavour is particularly potent in truffles, a kind of subterranean fungus, which you might find hints of in mature Champagnes like Gosset, Extra Brut, Celebris, Champagne 2002 — where yeast influences deepen into umami fungi notes.

As well as oak aged Chardonnay such as Bouchard Père & Fils, Corton, Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru, Burgundy 1955, where mushroom is joined by other tertiary notes like lanolin and oatmeal.

Translated by ICY

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit