Get to grips with the some of the more obscure tasting notes used by wine experts, with graphics from the Decanter design team...

Lychee

With their spiky red exteriors and translucent white flesh, lychees are one of the more exotic fruit varieties in the wine lexicon. They’re defined by a mildly sweet fruit flavour, with an edge of tartness and a floral aroma.

Their large central seed makes lychees look similar to stone fruits, but when it comes to wine they are classed among the tropical fruit flavours — joining mango, banana, passion fruit and pineapple.

Lychee notes are typically found in white wines, often those with subtle fruit flavours and spicy or floral characteristics.

A classic example is Gewürztraminer wine, described by Thierry Meyer, DWWA Regional Chair for Alsace, in Gewurztraminer to change your mind:

‘It smells of ginger and cinnamon, fragrant rose petals and pot pourri with a dusting of Turkish Delight and tastes of deliciously exotic lychees and mango.’

These wines are commonly made in cool climate regions like Alsace and Alto Adige in northern Europe, as well as Marlborough in New Zealand.

SEE: Lidl, Gewürztraminer Vieilles Vignes, Alsace 2016 | Gewürztraminer, Alto Adige, Trentino-Alto Adige 2014 | Yealands Estate, Gewürztraminer, Awatere Valley, Marlborough 2010

Other aromatic white wines with lychee notes could include Sauvignon Blancs, such as Massey Dacta, Marlborough 2015, which combines minerality with tropical fruits.

As well as Pinot Grigio, Prosecco and Soave wines from northern Italy, Austrian Grüner Veltliner and Torrontés from the lofty heights of Salta.

SEE: Cantina Tramin, Unterebner Pinot Grigio, Alto Adige 2014 | Sommariva, Brut, Conegliano-Valdobbiadene NV | Bolla, Retro, Soave Classico, Veneto 2011 | Bodega Colomé, Colome Torrontes, Calchaqui Valley 2015

Medicinal

Although ‘medicine’ might seem like a broad category, the wine descriptor medicinal usually refers to common everyday products, like cough syrup or ointments. In these medicines, acrid chemicals are often covered with more palatable flavourings and sweeteners. This often creates a product that’s superficially sweet or herbal, with an underlying chemical bitterness.

In this way it’s related to other notes in the herbal category of the wine lexicon: lavender, mint and eucalyptus — all have a bitterness overlaid with pungent natural oils.

A medicinal whiff in your wine could indicate the presence of Brettanomyces yeasts.

Some wine lovers enjoy Brettanomyces’ effects at low levels, such as in some styles of Beaujolais, but it’s a cause of debate and others view ‘brett’ as a fault.

Medicinal notes can also indicate smoke taint, which can arise from high toast levels in oak barrels, according to the Australian Wine Research Institute.

On the plus side, a medicinal hint can develop with ageing and give some red wines a desirable complexity, comparable to other unusual notes like vinyl or tar. You can look for it in some red Bordeaux blends.

Medicinal characters can also be present in Australian Shiraz, where it can integrate well with black fruit, spicy and smoky flavours.

However, if not balanced correctly it can dominate the wine: Larry Cherubino, The Yard Acacia Vineyard 2015 Shiraz from Frankland river, for example, was partially noted for its ‘overpowering’ cherry medicinal tone in a previous tasting.

An over-bearing medicinal flavour may also suggest that the wine is ‘tiring’ and losing its fruit, as Andrew Jefford noted last year on one Pomerol 1982 wine.

Rose

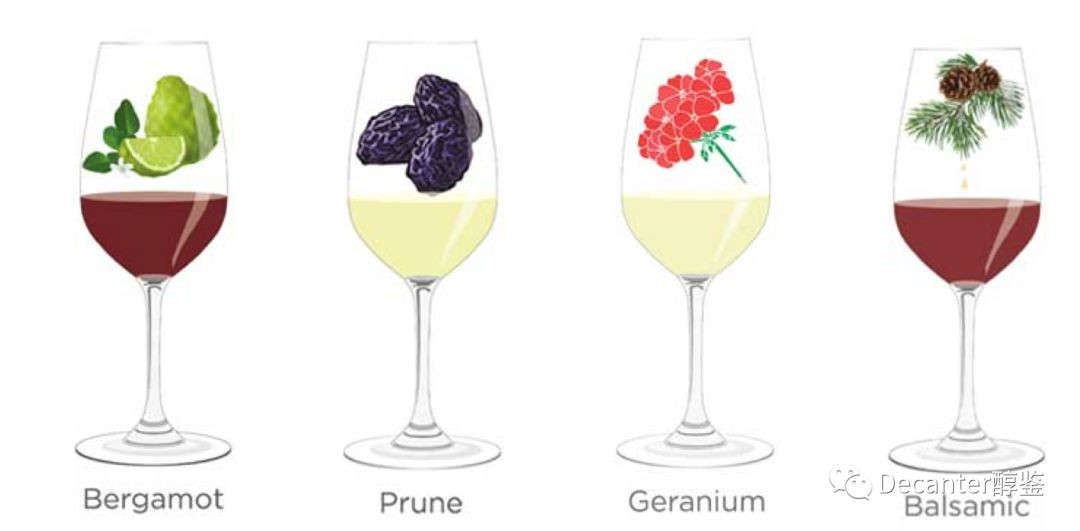

As with many floral notes in wine, rose is sweet on the nose but more bitter and austere on the palate. In this way it’s comparable to notes of violet and magnolia, stopping short of the slight acridity of lily or geranium.

You may find the flower referred to directly or as ‘rose petal’, as well in the form ‘rose water’ — which suggests it smells more like musky perfume, or tastes a bit like Turkish Delight.

The science behind rose’s flavour profile comes down to 3 key chemical compounds: rose oxide, β-damascenone and β-ionone.

Usually it’s the rose oxide element that makes it comparable with the smell of some Gewürtztraminer wines. They’re known for their highly aromatic qualities and signature lychee notes — a fruit which carries the same rose oxide compound.

SEE: Jean Cornelius, Gewürztraminer, Alsace 2015 | Paul Cluver, Gewürztraminer, Elgin 2015

β-ionone is also behind the aroma of violets, so it makes sense that violet-scented wines can sometimes harbour rose hints too — such as red wines made in Piedmont from the thick-skinned Nebbiolo grape. You can also look for rose notes in young Pinot Noir wines, particularly those made in Australia and New Zealand.

SEE: Henschke, The Rose Grower Nebbiolo, Eden Valley, Australia 2013 | Giovanni Rosso, Serra, Barolo, Piedmont, Italy 2012 | Pegasus Bay, Pinot Noir, Waipara, New Zealand 2013 | Deviation Road, Pinot Noir, Adelaide Hills, Australia 2012

Note: Rose as a tasting note has little to do with rosé wines, which are named after their pinkish colour rather than for a floral character (see Spanish rosado and Italian rosato equivalents).

Rubber

Rubber is one of those tasting notes that can be difficult to imagine in a wine, but once smelt it’s unmistakable. You can find it in the aromas of certain Syrah wines from the northern Rhône, where it can appear alongside earthy, gamey or tar notes.

Or it can be found among petrol aromas associated with dry Riesling wines, particularly those from cooler climes such as Germany’s Rheingau region.

SEE: Delas, Francois de Tournon, Saint Joseph, Rhône 2010 | Maison Guyot, Le Millepertuis, Crozes-Hermitage, Rhône 2010 | Weingut Knoll, Riesling Kabinett, Pfaffenberg, Niederösterreich 2013

Burnt rubber on the other hand, can point to the presence of mercaptans, which are volatile sulphur compounds. But how does sulphur get into your wine? The truth is grapes themselves already contain sulphur, and sulphur compounds can be generated through reductive reactions involved in winemaking, such as yeast fermentation or malolactic fermentation. Mercaptans are not harmful, but they can become a fault if too concentrated — decanting the wine first can help to lessen their effect.

Volatile sulphur compounds have become a hot topic in winemaking in recent years. They have proved a particular source of controversy in some wines, notably in relation to burnt rubber aromas in some South African Pinotage and Cabernet wines. Today, growers increasingly try to avoid this, aiming for more fruit forward wines.

In the tasting note lexicon, rubber belongs to the mineral flavour profile, which includes anything ranging from earth to tar, and steel to wet wool. The best way to learn to recognise these notes in wine is to experience them in their physical forms, such as smelling a rubber eraser or car tires on a hot day (burnt rubber) — try to embed these aromas in your sensory memory.

Translated by ICY

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit