The man behind Beijing airport’s Terminal Three and Hong Kong icons Chek Lap Kok airport and the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank building, is turning his hand to a rather more intimate project: reworking a chateau in the Médoc that receives on average 8,000 visitors per year – not far from the number Beijing airport manages in one hour.

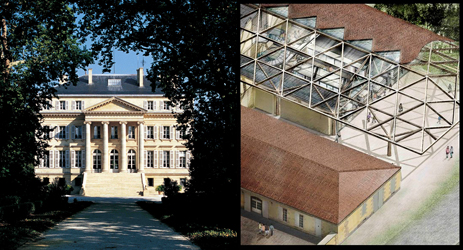

This is not, of course, just any chateau. The Foster + Partners project, which has now received all the necessary planning permissions and will get underway in April 2013, is with Chateau Margaux, the 1855 First Growth whose building is an historic monument that has been unaltered externally since construction in 1810 by Guy-Louis Combes, rather appropriately the star architect of his day.

Combes and Foster parallel each other in other ways. Both came from modest backgrounds, were recipients of architectural prizes throughout their careers but remained revolutionaries in their own way. Combes was known for his political views and attachment to the revolutionary ideals, and his buildings were unconstrained by the accepted norms of the day. Foster equally seems to take on projects that bypass expectations. In his restoration of Berlin’s Reichstag, for example, he designed a method of powering the building with vegetable oils, reducing carbon-dioxide emissions by 94 per cent.

Then again, the multi-award winning Foster may have been enticed to Bordeaux because he enjoyed his previous winery project, Bodegas Portia in Spain. Or because he wanted to make his own stamp on what seems to be the latest destination for top-flight designers and architects, more than a little reminiscent of Rioja in the late 1990s. Among Foster's contemporaries leaving their signature on Bordeaux are Philippe Starck, Jean Nouvel, Christian de Portzamparc, Herzog and de Meuron, Albert Pinto, among a host of others.

Foster is one of the rare architects to have become part of our psychological as well physical landscape, punctuating our lives with buildings that point to the audacity and sheer optimism of leaving something permanent behind. So why would a man so used to dealing with vast multi-billion pound projects choose to take on a winery? 'Wine and art are my great passions,’ he replies simply, ‘and as a lover of wine, Chateau Margaux is a hallowed label.’

His approach to the project was, however, as with any other – through exhaustive research and preparation. ‘The principal challenge is how can the architecture capture the spirit of a wine and the place that nourishes it. Then there is the issue of balancing the demands of production with the need for flexibility and the creation of new spaces for visitors,' says Foster. 'We begin every project with a period of intense research. With our winery projects, this has involved following the different stages of the wine-making process from harvest to tasting, listening to the winemakers, learning about the grape – as a lover of wine, for me this was a labour of love.’

‘Our winery for Faustino in Spain’s Ribera del Duero region may have become symbolic of the wine, but its striking form was generated by analysis of the site, the process of wine-making and the different functions it would contain. These were higher priorities than a desire to make a statement. The three main stages of wine-making – fermentation in vats, ageing in barrels and maturation in bottles – define the three wings of the building. The ends of these wings touch the earth, keeping the building’s profile low in the rural landscape and creating a ramp for tractors to drive onto the roof. From here the grapes are dropped down into the vats, thus reducing the damage to the harvest and helping to improve the quality of the wine.’

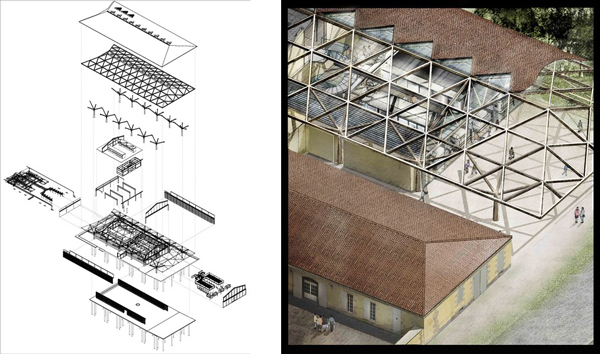

The challenge was different for Chateau Margaux as a listed building, and as a place that already comes with its own symbolism. 'Margaux produces exceptional wine. And the chateau already has an exceptional ‘look’ – our project also includes the restoration of the impressive Orangerie, the oldest structure on the estate. For me, the industrial buildings (of the existing chateau) are equally remarkable. Ever since I was a student, I have been fascinated by simple barn buildings – the “architecture without architects”, as Bernard Rudofsky called it. In my design for Chateau Margaux’s new winery, I have been inspired by the traditional clay tiled roofs in the surrounding villages. The new building will be a very discreet addition, in harmony with the existing timber structures.’

‘We have worked with of a number of protected buildings around the world, from the Reichstag in Berlin to the British Museum in London. This work has often involved revealing the underlying architectural logic of a building by peeling away unnecessary historical accretions, and a combination of restoration and new construction.’

The historical logic to Margaux was clear – the estate was planned as an entire farming village, as were most of the large Médoc properties, built at a time when roads were poor and most staff – from chefs to vineyard workers to barrel makers – would live permanently on site, surrounded by the facilities needed for wine-making. ‘Our design retains this connection between process and architecture,’ notes Foster. ‘The existing buildings are being restored to their original design intent and in some cases given new functions. A new winery extends from the eastern wing to balance the overall composition. In its simplicity, this highly flexible, open enclosure reinterprets the form of the original industrial buildings. It has a pitched roof at the same level, supported by load bearing columns and punctuated by light wells. Its design is a natural successor to the vernacular tradition of the big roofed agricultural buildings of the region, but uses today’s technology and construction methods.

With work set to start next month, the team at Margaux should be making wine in the new buildings for harvest 2014. This is a big project, but one that is needed, and they are keen to get underway. Foster will be sharing some of the day-to-day work with a Bordeaux architectural firm, but will be on site regularly over the 18 month build – and if he’s stuck for a lunch partner, should have no trouble finding a fellow architect to join him. And if Bordeaux is in danger of becoming the new Rioja, Foster is not about to complain about it. ‘If architecture has a role to play in encouraging people to discover the origins of wine, then this can only be positive. But we are not driven to create icons. Our designs are driven by the wine-making process.’

Columnist Introduction

Jane Anson is Bordeaux correspondent for Decanter, and has lived in the region since 2003. She is author of Bordeaux Legends, a history of the First Growth wines (October 2012 Editions de la Martiniere), the Bordeaux and Southwest France author of The Wine Opus and 1000 Great Wines That Won’t Cost A Fortune (both Dorling Kindersley, 2010 and 2011). Anson is contributing writer of the Michelin Green Guide to the Wine Regions of France (March 2010, Michelin Publications), and writes a monthly wine column for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she lived from 1994 to 1997. Accredited wine teacher at the Bordeaux Ecole du Vin, with a Masters in publishing from University College London.

Click here to read all articles by Jane Anson>>

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit