‘First jury duty I have been upset to be turned down for,’ said one tweet from a New York wine merchant in late March 2013, as the eight-strong jury was selected for Koch vs Greenberg.

Like most of the wine industry, I knew exactly what he meant. This was one of the big wine fraud trials of the year, a warm-up for Rudy Kurniawan, which is currently expected to get underway in September. The case was being held before Judge J Paul Oetken, and involved billionaire William Koch - ex-America's Cup winner and CEO of energy conglomerate Oxbow Group - suing Eric Greenberg on fraud and breach of trust charges. Koch was claiming that 24 bottles of wine purchased by him from Greenberg (via Zachys auction house) were counterfeit. Greenberg in turn was denying wrongdoing, arguing that the bottles of wine were sold at auction ‘as is’, and that he had no idea that the bottles were not what they purported to be.

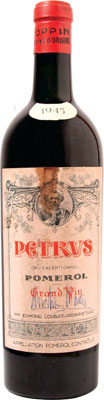

The two sides were flanked by a full 22 attorneys, led by Robert Darby and John Hueston for Koch and Arthur Shartsis for Greenberg. The case hung on whether these bottles – among them two magnums of Cheval Blanc 1921, a Petrus 1928, a Lafite 1811, a magnum of Lafite 1945, and a series of magnums of Chateau Lafleur - were indeed forgeries, and whether Greenberg could have reasonably believed them to be real.

On April 12, after three weeks in the courthouse for the Southern District of New York, near City Hall and the Brooklyn bridge in Lower Manhattan, Koch walked away with US$12 million in damages. He had initially sought US$320,000 in compensation – which he received, with the rest in ‘punitive damages’ effectively given as a bonus. ‘We weren’t expecting damages and we got $12 million,’ Koch said after court, ‘so it’s unbelievable.’

What had started out as a civil trial between two billionaires squabbling over 24 bottles of wine had turned into a huge success for Koch’s legal team – and had shone the spotlight on one softly-spoken Englishman who is fast becoming the go-to ‘gun for hire’ in wine fraud cases.

Koch first approached Egan in 2007, after learning of his work with Russell H Frye against Californian wine merchant The Wine Library. Frye accused The Wine Library of selling him more than 30 bottles of fake wine, at least some which were obtained from notorious wine forger Harry Rodenstock. The case reached an out of court settlement, but Egan’s expertise was obviously noted by Koch, and he called on his help for the case against Greenberg.

In November 2010, Egan was brought over to inspect Koch’s cellar in Osterville, Cape Cod, to look over the suspect wine. He examined 36 bottles and found all but one to be fake. They were good, sophisticated fakes, and could have fooled a lot of people, but not an expert such as Egan. He prepared a report, filed his deposition in July 2011 (also in Cape Cod, at the yacht club this time. A court stenographer was taking down minutes, but no judge was present). During the trial itself, he spent six hours in the witness box.

Becoming a world expert in wine forgeries is not, I would imagine, a career that you fall in to. Egan has certainly earned his stripes: he worked at Sotheby’s from 1981 to 2005, and when he left he was called upon by private collectors to review their cellars, and speak as an expert witness in any resulting investigations. I have been told that he is often banned from auction rooms, as the auctioneers are concerned at what he might find.

By the end of 1982, Egan became a cataloguer, then senior cataloguer, then deputy director and was director by 1995, working alongside Serena Sutcliffe. And by the mid 1990s, spotting fakes had become a serious part of Egan’s job. 'You have to remember that forging wine is not as hard as forging a major work of art. It requires quite a low capital outlay initially, and the technology required for a long time was not extensive. In the beginning of the 1980s, everything was done on trust. If a wine with a damaged label came in, we would send it back to the chateau or they would send over a good label to replace it. At this time, and at its height in the last 1980s, many chateaux – particularly Lafite and Mouton – were doing a lot of re-corking. They would travel, and do it in New York, Paris and other cities, for free, as part of the service to their customers. They would put a strip on the back saying ‘Reconditioned by the Maitre de Chai on X date’ but would make no other record. Bottles of the same type began to appear on the auction circuit, as these were easier to fake than the original bottles. By the mid 1990s, forgeries seemed to be on an organised scale, particularly of Lafite and other key Bordeaux properties such as Petrus and Lefleur.'

In the Koch trial, the forged bottles were in the courtroom, presented to the jury by the lawyers while Egan was in the witness box, explaining how to spot they were not the real deal. ‘Many of the bottles dated from the war years, when estates or négociant houses would not have been producing this many magnums. Or the glass bottle was older than the wine purported to be inside it; the 1921 Lafite had a hand-blown bottle, but by the 1920s glass making would have been mechanized and there would have been a seam visible. In other cases the labels had been artificially aged, using paper that was not as fine as it should have been. I had seen many of these wines when inspecting cellars during my 24 years at Sotheby’s, and I know there are certain key mistakes to look out for.’

In the meantime, Egan will continue to inspect both private and professional cellars, mainly in the US and Europe, and more recently in Macau – ‘names are always confidential of course. No one wants their clients to think they have fake wines in their cellars, but many are getting worried. If you’re looking at a large format, pre-1950 bottle of a celebrated Bordeaux wine, my estimate is that you have a 70-80% chance of it being a fake.’

Columnist Introduction

Jane Anson is Bordeaux correspondent for Decanter, and has lived in the region since 2003. She is author of Bordeaux Legends, a history of the First Growth wines (October 2012 Editions de la Martiniere), the Bordeaux and Southwest France author of The Wine Opus and 1000 Great Wines That Won’t Cost A Fortune (both Dorling Kindersley, 2010 and 2011). Anson is contributing writer of the Michelin Green Guide to the Wine Regions of France (March 2010, Michelin Publications), and writes a monthly wine column for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she lived from 1994 to 1997. Accredited wine teacher at the Bordeaux Ecole du Vin, with a Masters in publishing from University College London.

Click here to read all articles by Jane Anson>>

- Follow us on Weibo @Decanter醇鉴 and Facebook

and Facebook for most recent news and updates -

for most recent news and updates -

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit